The most important number in the World

About “the Climate Clock” and the Circular Economy as a feasible solution to enact transformational changes.

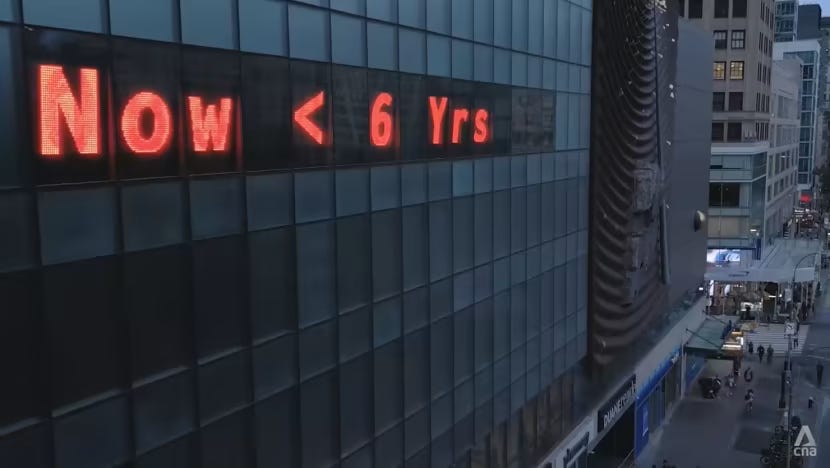

The most important number in the World…

I am not referring to your bank balance, BitCoin account password, or cholesterol level, but to the number displayed on the Climate Clock. Its countdown serves as a stark reminder of the dwindling time we have left to avert climate disaster. And it is now slightly less than 5 years…

You may be aware that in 2023, Earth experienced its warmest average surface temperatures since NASA/GISS records began in 1880. Earth was about 1.36°C hotter in 2023 than in the late 19th-century (1850-1900) preindustrial average. The 10 most recent years have been the warmest on record. In 2024, we expect to break previous records with the highest daily global average temperature reached on July 22nd (Climate Copernicus, 2024).

This is mainly due to Greenhouse gases (GHG), especially Carbon Dioxide (CO2) emissions from burning fossil fuels as Professor Svante Arrhenius suggested already at the end of the 19th century (!).

A critical threshold.

In 2015, during Paris COP21 (UN Climate Change Conference), 196 Parties adopted a legally binding international treaty on climate change with a clear goal:

to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”. (UNFCCC, n.d.)

More recently, world leaders have stressed the need to limit global warming to 1.5°C by the end of this century.

Why is the 1.5°C threshold so important?

Crossing the 1.5°C threshold will unleash far more severe climate change impacts than we are currently experiencing - such as frequent and severe droughts, heatwaves, rainfall, etc. To limit global warming and preserve a livable planet, recently the EU Commission with the European Green Deal set ambitious goals: EU countries need to reduce GHG emissions by at least 90% by 2040, compared to 1990 levels, and have to reach Net Zero by 2050.

What does “Net Zero” mean?

“Net Zero” does not mean we should not produce any CO2 emissions.

It means “cutting carbon emissions to a small amount of residual emissions that can be absorbed and durably stored by nature and other carbon dioxide removal measures, leaving zero in the atmosphere.” (UN, n.d.)

(Not really) Transitioning to a “Net Zero” World…

We are far from this objective. The pace of emission reduction needs to pick up, to almost triple the average annual reduction achieved over the last decade.

No pressure!

The Climate Clock serves as a daily reminder that time is running out: as previously said, at current rates of GHG emissions, we have less than 5 years left in our global “carbon budget” to have a two-thirds chance of staying under the critical threshold of 1.5°C of global warming (Climate Clock, n.d.).

Transitioning to a net-zero world is one of the greatest challenges humankind has faced. It calls for nothing less than a complete transformation of how we produce, consume and move about (UN, n.d.)

What about the available solutions?

The (Happy) Degrowth Theory

Some politicians and economists state we need to drastically reduce production and consumption levels to scale back the global consumption of limited resources. This is the concept of degrowth.

Degrowth means shrinking rather than growing economies, so we use less of the world’s energy and resources and prioritize wellbeing over profit. (WEF, n.d.)

Put another way: Government policies have focused on growing and expanding economies ever since, causing progressive global warming (which, according to scientists, started coincidently around the 1830s when the first industrial revolution peaked).

The solution is to move away from the equation: growth = good.

One thing the degrowth supporters are extremely right about: we need to reconsider GDP as the only key performance indicator of human “progress.” We need to decouple the concepts of “growth” and “progress.” We need to rethink the meaning of progress1.

Degrowth, especially the “happy” kind, is not really feasible.

Developed countries, responsible for the majority of GHG emissions, cannot effectively ask all Countries, including developing ones, to cut down production and consumption, thereby stopping their development process, only because some of the first polluters of the World are now fighting the consequences of their uncontrolled growth.

Moreover, a reduction in production and consumption—and therefore in GDP—will not necessarily result in cleaner and more efficient production processes.

A decline in financial resources could lead to industrial regression, where obsolete and more environmentally damaging technologies are preferred over innovative ones that allow for greater preservation of the environment (consider the recent comeback of coal among energy sources).

On the other hand, as GDP increases, increasing financial resources are invested in research and development aimed at making industrial production cleaner.

Degrowth theory ignores the potential of innovation as an engine of development, which Circular Economy (CE) leverages.

Circular Economy as a feasible solution to reduce GHG emissions.

The 2021 Circularity Gap Report claims that a CE could reduce global GHG emissions by 39%, making material flows more efficient and maintaining the utility and value of materials and products for as long as possible. On a global scale, nearly 70% of CO2 emissions are related to the extraction and processing of raw materials. CE attempts to design out waste and reduce raw materials consumption by extending product lifespan, reducing material losses, recirculating materials and products, preventing downcycling and substituting GHG-intensive materials with those with lower emissions. This seems a much better approach to the problem.

Implementing Circular Economy: practical applications.

The energy sector generates around three-quarters of GHG emissions today, boosting climate change. Replacing polluting coal, gas, and oil-fired power with energy from renewable sources, such as wind or solar, would dramatically reduce carbon emissions. This is CE in practice.

The building sector is another significant polluter with an important role in achieving climate neutrality. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, by applying CE principles2 to the design of buildings, infrastructure and other elements of the built environment, it is possible to reduce GHG emissions by 38% by 2050 while creating urban areas that are more livable, productive and convenient. CE helps the building industry to reduce demand for raw materials like steel, aluminium, cement, coil, making the sector more resilient to supply chain disruptions and price volatility.

The golden formula: feasible and profitable.

"Transition towards a circular economy is estimated to represent a $4.5 trillion global growth opportunity by 2030, while helping to restore our natural systems.” (EllenMacArthur Fundation, 2019)

CE appears to be a much more feasible approach to GHG emission reduction, supporting the achievement of the Paris Agreement targets and preserving the livability of our planet. Additionally, it brings other advantages: carbon reduction, realized by implementing CE principles, generates savings—like reduced energy bills and better supplier agreements—which can affect industry profits by up to 60% (McKinsey, 2019).

The essential role of consumers.

The responsibility is not all on the industry’s shoulders. People must play their part by buying less, but most importantly, by choosing to buy better (circular, truly sustainable) products. Only a combined, “multi-sided” approach, as well as a radical shift in perspective, would lead to a positive impact.

Thank you for reading till the end. If you would like to know more about the consumer’s role in the sustainable transition, as well as how to improve consumption or manufacturing decisions, keep following “The Butterfly”.

Keywords: Paris Agreement, Climate Clock, Net Zero, Degrowth Theory

Music pairing: “Time is Running Out” - Muse

This would be another interesting topic. I suggest reading the book “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist” by Kate Raworth (no adv)

Some potential CE actions may be 3D printing of building elements, improved maintenance to extend a building’s lifetime, innovative concrete formula and production processes, not to forget the use of renewable energies for heating and cooling systems.